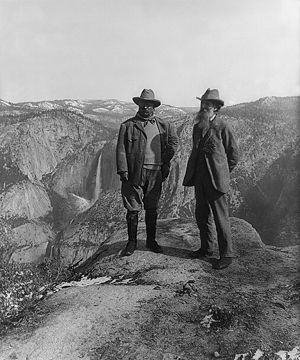

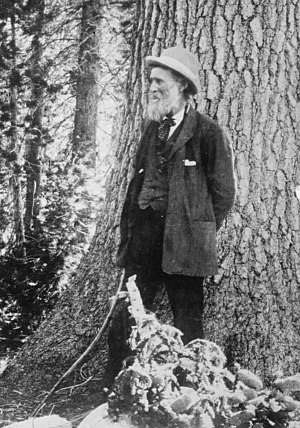

U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (left) and nature preservationist John Muir, founder of the , on Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park. In the background: Upper and lower Yosemite Falls. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The first argument about preserving versus developing wilderness was the fight over the Hetchy-Hetchy Reservoir in California’s Yosemite Park which erupted in 1908. Opposition to the development of a new water system for San Francisco was led by the Sierra Club, which had been founded by John Muir in 1892.

Muir was originally an easterner who was closely associated with Roosevelt and other early conservationists, but he was not a hunter and his motivation to preserve natural spaces did not grow out of a desire to conserve animal habitat so much as to preserve wilderness areas. But as the country continued to grow and the space between the Missouri River and the West Coast was filled in, the issue of wilderness versus development could not remain a back-room debate for the simple reason that there was too much at stake. Once railroad lines stretched not only from coast to coast but throughout the interior itself, the resources of the frontier zones – crops, animals, timber – were simply too abundant and could be moved to market too cheaply to resist exploitation by commercial interests on both coasts.

The early conservationists, including Roosevelt, acknowledged the inherent conflict between maintaining natural space on the one hand and retarding economic growth on the other. But as the conservation movement morphed into environmentalism, a wedge was driven between the two movements that claimed management responsibility for as-yet undeveloped space, a wedge based on one question: what should be the role of government in managing the natural patrimony?

For hunters/conservationists, government’s role was to be limited to enforcing rules that regulated the relationship of hunters to wild game: giving hunters access to hunting areas, restricting the hunt to periods that would allow the natural migration and reproduction of species. Environmentalists, on the other hand, wanted government regulation to cover the entire natural patrimony; not to control the behavior of hunters who otherwise might threaten wildlife, but to control the behavior of developers who otherwise might threaten the entire environment.

What we have ended up with is the notion that wilderness preservation versus economic development are inextricably opposed; that you either wind up with one or the other. Every development initiative is a threat to nature, every preservation plan is an effort to derail economic development. The fight over the Keystone pipeline is the argument in its current form.

The origins of the fight go back to 1890 when the Census declared the wilderness to be closed. But the United States was the only country in the entire world that industrialized and closed its frontier at the same time. In Europe, the wilderness disappeared a thousand years before the Industrial Revolution began. In America we were laying railroad track and slaughtering buffalo at the same time.

The truth is that our extraordinary economic development took place not as a conflict with nature, but because we were able to tap the abundant resources of nature for the first time. Urban centers that appeared in Europe during the 19th century competed for building materials that had to be expensively extracted and shipped from distances far and wide; Chicago was built from wood that floated down from Wisconsin.

Ten years after we closed our frontier the output of our national economy surpassed the combined production of all the other industrialized economies combined. The resources that fueled American economic development were so cheap that re-investment and further growth could occur at three or four times the rate experienced in other industrializing zones. The greatest irony is that the self-same conservationists, like Roosevelt and Grinnell, who mourned the disappearance of wilderness came from the elite class whose economic fortunes derived from the resources extracted from the wilderness itself.

This is the 3rd and final summary of our fourthcoming book on hunting and conservation to be published by the end of the year.

- NeverEnding Stories: Commerce Versus Conservation (wnyc.org)

- WILD10 Indigenous and Community Land and Seas Forum Schedule (firstpeoples.org)

Recent Comments